In stark contrast to my last post, I just wanted to touch on a few topics briefly today without getting too involved. These were just a couple of interesting topics that I got into this past weekend.

Women's Scaling:

CrossFit HQ has asserted in the past that there are no "prescribed" women's scaling options for their workouts. According to HQ, each workout should be scaled to the particular athlete's abilities. I'm not going to argue with that sentiment here, at least as it applies to training. But the fact is that HQ does scale the weights differently for men and women during competitions, and most, if not all, local CrossFit competitions do the same. But are they scaled fairly?

Counting the Outlaw Open (Dec. 1-2), I've now analyzed seven different competitions from the past two years (the other six are the Open, Regionals and Games from 2011-2012). What I wanted to look at now was the average relative weight on metcons and the load-based emphasis on lifting (LBEL) in each competition for both men and women. What I found was this:

For metcons, the average relative weight for women has been between 61-71% of the men's load. In total, the LBEL (which includes all events) has been between 61-69%. That's not a huge spread, but it could mean the difference between programming cleans at 95 lbs. and 110 lbs.

To see if there was an "optimal" relativity between men's and women's weights for CrossFit competitions, I decided to look into the (few) non-metcon lifting events we've had in those competitions. In those seven competitions, there have been three max snatches, two max cleans, one max thruster, one max bench and one 5-rep max deadlift. Taking the average of the field in each of those events, the women's results were between 51-65% of the men's. The 51% was on the bench at the Outlaw Open - my theory on the bench being so much lower is that a lot of emphasis is placed on the bench in many men's sports, including football (just a theory though). Other than bench, all others were between 58-65%. Considering that the average female competitor at the 2012 Games weighed a shade under 75% of the average male competitor, I'd say those are some damn impressive strength numbers.

If those maxes are a decent indication - and I think they are - then the programming should generally be looking to keep the women's weights at around 60-62% of the men's. And in fact, things appear to be moving toward that. In 2011, the women's loads in the Open, Regionals and Games were between 66-71% of the men's (using either LBEL or average metcon weight); in 2012, they were between 61% and 68%. At the Outlaw Open, the LBEL was 62% of the men's and the average metcon load was 65%.

This all assumes that the goal is to make the women's events just as challenging for their field as the men's events are to their field. For the most part, bodyweight movements are not scaled at all for women, which helps explains why in the 2012 Games, the average women's time on metcons was still about 20% slower than the men's. But perhaps that's not a problem. I think a lot of the draw for women's competition is seeing these women doing virtually the same thing as the fittest men in the world. I'd venture to say the top women are about as proficient at muscle-ups as the top men were just 3 or 4 years ago, if not more proficient. And at the Outlaw Open, the average max-rep set of pull-ups (after two miles of running and a 5-rep max deadlift) for the women was 33, just 9 behind the men.

Outlaw Open Notes:

The Outlaw Open is the first non-HQ sponsored competition that I've analyzed, so I thought it would be interesting to see how it compared to the Open, Regionals and Games, and also, what we can learn about the athletes who competed there (and there were some heavy hitters).

First, this won't come as much of a shock, but the Outlaw Open was heavy. Real heavy. The average relative weight on metcons for the men's competition was a 1.45*, which is 23% higher than the highest we've seen in the Games or Regionals. To give you a feel of what a 1.45 means, these are the types of weights you'd see in an average metcon:

Clean/Jerk - 195

Snatch - 145

Deadlift - 350

Thruster - 160

Overhead squat - 165

Back squat - 275

Front squat - 232 (we actually saw 250 in a metcon here)

The average weight for the women's competition was 0.95, which is higher than the average load in the men's Open in 2011. You may want to read that last sentence again to let it sink in.

In terms of LBEL, which takes into account max-effort events as well as the portion of the competition that was weighted/unweighted, the men's Outlaw Open came in at 0.94. That's just a shade below the 2012 Regionals, the highest in an HQ competition. The LBEL gives a better indication of whether a competition "favors" bigger athletes, so the inclusion of more bodyweight movements (in total the split was 50/50 between bodyweight and lifts) helped to balance things out. It's interesting to note that the men's CrossFit Invitational had an LBEL of 1.20, although that was a team competition so it's not exactly an apples-to-apples comparison.

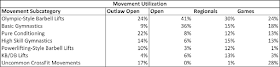

As far as the types of movements involved*, here's how the Outlaw Open stacked up against the Open, Regionals and Games the past two years.

This kind of blew my mind that an Outlaw competition actually included Olympic lifts as a relatively modest portion of the scoring (I did take into account the points available on each event). So while the weight levels may have been most similar to the Regionals, the types of movements were distributed much more like the Games.

So what can we learn from the Outlaw Open? Well, clearly given the level of competition, anyone finishing well has to come away feeling good about their preparations for the upcoming season. I tend to think this will be most predictive of performance at the Regional level (vs. the Open or the Games), although we didn't see any lighter, higher-rep, grinding metcons, and the Regionals have had one of those the past two years. But if the Regionals are once again heavy, I think you'll see the top athletes from this competition with a good shot to get to the Games. Did someone say "vindication for Matt Hathcock?" We shall see...

*Assumptions on base weights for non-standard movements:

Wheelbarrow - 240 (same as deadlift)

Double KB thruster - 44 each arm (assumes DB's are 2.25x as difficult as a barbell, and KB's are 1.1x as difficult as a DB)

Double KB snatch - 40 each arm (same assumption)

Barbell step-up - 95 (this one was purely a judgement call based on watching the athletes a bit)

I'm always looking for more data to refine these base weights, so let me know if you have reason to believe these are out of line.

**If you've read my last post, you'll see that that I now have eliminated "Medicine Ball Lifts." I moved wall-balls into KB/DB lifts (I felt they are most similar to a DB thruster) and moved all other movements involving a medicine ball/slam ball (medicine ball cleans, ball slam, GHD ball toss, etc.) to "Uncommon Crossfit Movements."

A look at the CrossFit Games from a statistical, dare I say actuarial, perspective. A blog by Anders Larson, FSA, MAAA.

Monday, December 10, 2012

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Does Our Training Look Like What We're Training For? Should It?

OK, well I think it's time to try and tackle one of the most complex subjects in the sport of CrossFit: training. About two months ago, I posted an analysis of the past two Games seasons, looking at what types of movements we've seen, the relative weights we've seen, and what we're likely to see this season. I think there was good insight to be gained from that piece, but I did not intend it to be interpreted as an instruction on how we should be training. I was simply looking into what it is CrossFit HQ is testing.

But the natural follow-up question is this: If performing well in the Open is our goal, should our training look like the Open as well? If performing well at Regionals is our goal, should our training look like what we'll see at Regionals?

I'm going to try and approach this in two parts. First, I want to look at this from a mathematical, somewhat theoretical perspective to see what we can learn that way. Next, I want to examine some popular and successful training regimens and see how they compare to the Open, Regionals and Games.

Part 1: A Theoretical Perspective

(If you absolutely hate algebra, I apologize in advance. This section contains some, but there's pretty much no way to understand the theoretical angle without it. Skip ahead to Part 2 if you must.)

Sometimes it's important to understand what we do not know. As I started working on this piece, my thought was that yes, for the most part, our training should look like what we are training for. If the Open is going to be 30% Olympic lifting, for example, then we should basically spend about 30% of our training energy on Olympic lifting, right? But as I started to think about this, I had a Lee Corso moment: "Not so fast, my friends."

Let's imagine a scenario where there are only two types of movements in the world: running and bench press (the Arnold Pump-and-Run world). If the competition we are training for features 70% bench press and 30% running, how should we split our training to maximize our performance? We will assume all events are scored separately and added together for a total score, so in our preparation, we want to improve our score as much as possible. In other words, we want to maximize this equation:

Improvement in Score = 0.70 * (improvement in bench press) + 0.30 * (improvement in running)

Now, let's assume at first that each hour spent training bench press can improve our bench press an equal amount. And we'll assume that each hour spent training running improves our running by this same amount. Let's now assume that we have exactly 5 hours per week to train, and each hour can score us 10 additional points in the events related to we are training for (keep in mind that the points in the running events are worth only 30% of total points but points in the bench press are worth 70% of total points). If this is the case, what should our training look like? Well, what we have now are two equations that define our improvement in bench press and running as a function of time spent. The way I have defined these, the graphs would look like a straight diagonal line angling up as you move to the right, and the equation for each would be:

Improvement in bench press = 10 * (hours spent bench pressing)

Improvement in running = 10 * (hours spent running)

Rewriting the second equation because we have a finite amount of time to train:

Improvement in running = 10 * (5 - hours spent bench pressing)

Now we can plug our two equations for the improvement into our original equation and try to maximize it. The equation we get is:

Improvement in Score = 0.70 * (10 * (hours spent bench pressing)) + 0.30 * (10 * (5 - hours spent bench pressing)) = (4 * hour spent bench pressing) + 15

I'll spare you the calculus, but the end result is that we would actually want to spend all of our time bench pressing if this were the case. Sure we wouldn't be "well-rounded," but we'd score the most possible points in the competition. Here's a chart illustrating our total improvement each week as a function of time spent bench pressing:

But the natural follow-up question is this: If performing well in the Open is our goal, should our training look like the Open as well? If performing well at Regionals is our goal, should our training look like what we'll see at Regionals?

I'm going to try and approach this in two parts. First, I want to look at this from a mathematical, somewhat theoretical perspective to see what we can learn that way. Next, I want to examine some popular and successful training regimens and see how they compare to the Open, Regionals and Games.

Part 1: A Theoretical Perspective

(If you absolutely hate algebra, I apologize in advance. This section contains some, but there's pretty much no way to understand the theoretical angle without it. Skip ahead to Part 2 if you must.)

Sometimes it's important to understand what we do not know. As I started working on this piece, my thought was that yes, for the most part, our training should look like what we are training for. If the Open is going to be 30% Olympic lifting, for example, then we should basically spend about 30% of our training energy on Olympic lifting, right? But as I started to think about this, I had a Lee Corso moment: "Not so fast, my friends."

Let's imagine a scenario where there are only two types of movements in the world: running and bench press (the Arnold Pump-and-Run world). If the competition we are training for features 70% bench press and 30% running, how should we split our training to maximize our performance? We will assume all events are scored separately and added together for a total score, so in our preparation, we want to improve our score as much as possible. In other words, we want to maximize this equation:

Improvement in Score = 0.70 * (improvement in bench press) + 0.30 * (improvement in running)

Now, let's assume at first that each hour spent training bench press can improve our bench press an equal amount. And we'll assume that each hour spent training running improves our running by this same amount. Let's now assume that we have exactly 5 hours per week to train, and each hour can score us 10 additional points in the events related to we are training for (keep in mind that the points in the running events are worth only 30% of total points but points in the bench press are worth 70% of total points). If this is the case, what should our training look like? Well, what we have now are two equations that define our improvement in bench press and running as a function of time spent. The way I have defined these, the graphs would look like a straight diagonal line angling up as you move to the right, and the equation for each would be:

Improvement in bench press = 10 * (hours spent bench pressing)

Improvement in running = 10 * (hours spent running)

Rewriting the second equation because we have a finite amount of time to train:

Improvement in running = 10 * (5 - hours spent bench pressing)

Now we can plug our two equations for the improvement into our original equation and try to maximize it. The equation we get is:

Improvement in Score = 0.70 * (10 * (hours spent bench pressing)) + 0.30 * (10 * (5 - hours spent bench pressing)) = (4 * hour spent bench pressing) + 15

I'll spare you the calculus, but the end result is that we would actually want to spend all of our time bench pressing if this were the case. Sure we wouldn't be "well-rounded," but we'd score the most possible points in the competition. Here's a chart illustrating our total improvement each week as a function of time spent bench pressing:

The maximum is all the way at the right side of the chart, meaning devoting all 5 hours to bench press. So clearly, if every moment of training were equal, what we would want to do is focus on the aspect of training that is emphasized more in competition. But in real life, every moment of training is not equal. What we see is diminishing returns, meaning that (in general), the value of each additional moment of training a particular movement declines the more we train that movemen. For instance, if you train your bench press 1 hour per week for 10 weeks, you may be able to bench press 15 more lbs. than you did at the start. But if you increase that to 2 hours per week, you may be able to bench press only 25 more lbs. than you did at the start. At 3 hours per week, you might be at 30 more lbs. Another way to phrase this is that the marginal effectiveness of an additional hour of bench pressing is declining.

In this case, our decision becomes more complicated. Depending on how quickly the marginal effectiveness declines for each movement, the graph of our improvement as a function of time spent bench pressing could look like one of these three curves (or plenty of others):

In these cases, the optimal time spent bench pressing (the pinnacle of each curve) could in fact be 50%, 70% or 80%. In general, the more quickly the returns diminish on each exercise, the closer you'll want to be to an even split between movements. But to my knowledge, we do not yet know what these functions are in reality (and they almost certainly vary depending on the skill level already attained). So even in this incredibly simplified scenario with just two movements, it is impossible to say with any certainty how much time one should spend on each exercise in training.

My feeling is that there are three key things we would need to know in order to determine the "perfect" balance between movements in your training program: 1) the scoring emphasis for each different movement (we do know this to some extent); 2) the amount of improvement to be gained on each movement, as a function of time spent on the movement (this can and probably will vary by movement); 3) the amount of "carryover" from one movement to the others (meaning that training the Olympic lifts might also improve the Powerlifting-style movements, or vice versa). There are some additional considerations with our sport, because you do have to have a minimum level of skill in every area, or else other areas can basically be rendered useless. If someone struggles mightily with toes-to-bar, their performance on 12.3 would be terrible even if they could push press 300 lbs. Still, I believe that, theoretically, we could also optimize these splits, as well as the splits between time domains and relative weight levels in a similar fashion. Potentially, careful research could eventually shed some light onto the second and third items, but at the current time, the best we can do is make educated guesses about them.

So while it seems like we may have learned nothing from this, we have indeed learned something: even if we know exactly what we are training for, we do not yet know the perfect way to train for it. To be sure, understanding what we are training for helps. The more Olympic lifting we are tested on, the more we should train it. But how much more? We (or at least I) just don't know for sure yet.

Part 2: How We Are Training

So we don't know the perfect way to train yet. That doesn't mean that some methods are not preferable to others. Some athletes have made great strides from year to year while others stagnated. There are coaches out there working extremely hard to understand the optimal ways to train, and we can learn from them. I'd like to look at the training for a few well-known CrossFit programs and see how they compare to the Open, which is what the vast majority of serious CrossFit athletes are training for (yes, there are maybe a couple hundred who can safely look past the Open to the regionals, but when guys like Rob Orlando are barely qualifying for regionals these days, overlooking the Open is a dangerous move for most).

Now, I understand that there are other great coaches and great programs out there besides the ones I am examining. Please do not skewer me if I have omitted your favorite. This work is time-consuming, and I do not mean to imply that these are the best programs by any means. They are just a few that I have followed to some extent in the past.

First, let's look at what it is we're training for. This is all based on the analysis from my prior post on what to expect from the Open, but I've grouped the movements into eight categories. A couple notes: 1) "Olympic-style Barbell Lifts" includes things like thrusters, overhead squats and front squats, which either help develop the Olympic lifts or have similar movement patterns and explosiveness (e.g., thruster); 2) "Pure Conditioning" includes running, rowing and double-unders; 3) "Uncommon CrossFit Movements" includes stuff that isn't on the main site often, like sled pushes, monkey bars or the sledgehammer. For a full list of what I've included in each, see the bottom of this post.

Additionally, here are a couple other metrics to help us understand the the load and duration of these workouts. I did not include the time calculations last time. For workouts that are not AMRAP, I have made rough estimates based on the average finisher (all max-effort workouts are in the 5:00 or under category, even if it was a ladder that spanned 8-10 minutes). Please see my last post on what to expect in the Open for more detail on how the others were calculated.

Again, let's mainly focus on the Open. That's what the vast majority of athletes are training for at the moment. Now let's see how these popular training programs compare.

First, some notes on how I handled the tricky parts of this analysis. For the purpose of this analysis, I have assumed that all strength or skill work that is performed in addition to a metcon is worth 0.5 "events." All metcons and all standalone strength workouts are worth 1.0 "events." The goal of this was to weight each part of the training program by how much mental and physical energy they took to complete, and for me, some strength work before a metcon does not tax me the same way the actual metcon does (or a standalone, main site-style strength WOD).

For strength workouts, I basically assumed that a max-effort lift was a 2.0 relative weight. If a percentage of the the max was used, it was multiplied by the 2.0. For strength workouts with a set number of reps, I assumed that doubles were at roughly 95%, triples at 90%, sets of 4 at 85% and sets of 5 at 80%. Beyond that, it was sort of a judgement call. Workouts calling for percent of bodyweight (like Linda) assumed a 185-lb. person.

For strength workouts, I basically assumed that a max-effort lift was a 2.0 relative weight. If a percentage of the the max was used, it was multiplied by the 2.0. For strength workouts with a set number of reps, I assumed that doubles were at roughly 95%, triples at 90%, sets of 4 at 85% and sets of 5 at 80%. Beyond that, it was sort of a judgement call. Workouts calling for percent of bodyweight (like Linda) assumed a 185-lb. person.

Now, for our first program, we will start where it all started: the main site (CrossFit.com). I'm not sure if any top athletes rely primarily on the main site these days, but it's still very popular for plenty of other athletes. I don't even know if Tony Budding or Dave Castro or whoever programs the main site would say that maximizing performance in the Open is even a goal of their programming. Regardless, we'll examine it.

The main site was the first program that I began tracking for this project, and it's also the easiest to track, because of the one workout per day set-up. I have used the past 6 weeks of workouts for this analysis.

The second program is CrossFit New England. I followed CFNE for some time and still sprinkle in workouts from their site in my own training pretty regularly. CFNE is not vastly different from the main site in its set-up, although they do program a decent amount of strength and skill work alongside the metcons. Note that this is not Ben Bergeron's CompetitorsWOD, and so this is probably tailored to a more general audience. I have used the past 3 weeks of workouts for this analysis.

The third program I looked at is The Outlaw Way. I have followed The Outlaw Way a bit, and coach Rudy Nielsen has produced plenty of Games-level athletes in the past few years. In my estimation, this program is the most competitor-focused of the ones we'll look at it today. And it was, without a doubt, the hardest of the programs to analyze. Rudy almost always programs one or two pieces of strength/skill work before the metcon, and so my assumption that these are worth 0.5 "events" is a significant one here. Still, I think we can gain some insight by trying our best to quantify what The Outlaw Way is doing. I have used just over 2 weeks of workouts for this analysis (sorry, but tracking these workouts is time-consuming - there were as many total movements used in 2 weeks as there were in almost 5 weeks of the main site!).

Finally, selfishly, I have thrown in my own training. I began this experiment by tracking my own training, and so since I already have the data ready to go, why not throw it in here, right? For what it's worth, I finished about 200th in my region (Central East) last year and am shooting to qualify for Regionals this year, although I know that's going to be tough. I train 3-on-1-off for about 60-75 minutes at a time. I have used the past 6 weeks of workouts for this analysis.

Let's see how these training programs compare to the Open.

As mentioned above, there is a good deal of judgement involved in compiling this data. Let's not read too much into small differences between programs and try to focus on the big picture. Here are some of my observations:

Going Heavy: All four training programs had a higher LBEL than the Open, and Outlaw was heavier by a wide margin (heavier even than the regionals). The difference seemed to come from the added strength work, because the actual metcons themselves weren't much different than the Open, besides Outlaw again.

Powerlifting: Although we don't actually see many Powerlifting-style movements in competition (back squat, deadlift, press, bench press), we do see it a lot in training. I recall a video where Tony Budding said that max efforts on slow lifts like the deadlift may not be appropriate for competition, but they are useful in training. This seems to be the case - across all competitions, they made up just about 4% of the points, but we're seeing 7-12% of emphasis in these programs.

Couplets and Triplets: We've heard it on the main site before that couplets and triplets (not longer chippers) should make up the bulk of your training, and it seems to be the case for these programs. It is interesting, however, that the main site averages significantly more movements per metcon that CFNE or Outlaw, neither of whom programmed chippers often. Prior work I've done ("Are Certain Events 'Better' Than Other") indicated that chippers were more predictive of overall fitness in competition, so I suppose the theory in training is that each of the movements gets "watered down" too much in a chipper. I'd be curious to know if there is solid evidence to back up this philosophy, although I tend to agree with it. UPDATE: Actually my previous post indicated that workouts with more movements tended to be more predictive of overall fitness, not necessarily that chippers were better than triplets or couplets. In fact, the "best" event through Open and Regionals was 12.3, a triplet.

Surprisingly Similar Balance Across Programs: I was surprised to see that each program generally put the emphasis on the same types of movements. Sure, the main site was a bit lighter on the Olympic lifting and heavier on the basic gymnastics, but in general, things weren't too different. Also note that none of the programs leaned as heavily on the Olympic lifts and basic gymnastics as the Open. Although...

Outlaw Lifts A Lot: One thing that doesn't show up on the comparison above is the total volume of training; it only deals with how the training time is divided. But it's worth pointing out that Outlaw's training goes through many more movements in a typical day than any of the others, and many of them are Olympic lifts. Below is a chart of the at a pure count of how many times the snatch, clean and jerk appeared, regardless of how much it was emphasized within the workout and allowing for multiple appearances in a day.

Keep in mind that the metcons at Outlaw are generally pretty short and the reps per set are generally low in the strength work, so the overall volume is not quite as intense as it may appear. And again, this is only two weeks worth of data. Also, CFNE's stats are a little inflated because they post a workout 7 days a week, and it's doubtful that many athletes are following the program completely without any rest.

Going Heavy: All four training programs had a higher LBEL than the Open, and Outlaw was heavier by a wide margin (heavier even than the regionals). The difference seemed to come from the added strength work, because the actual metcons themselves weren't much different than the Open, besides Outlaw again.

Powerlifting: Although we don't actually see many Powerlifting-style movements in competition (back squat, deadlift, press, bench press), we do see it a lot in training. I recall a video where Tony Budding said that max efforts on slow lifts like the deadlift may not be appropriate for competition, but they are useful in training. This seems to be the case - across all competitions, they made up just about 4% of the points, but we're seeing 7-12% of emphasis in these programs.

Couplets and Triplets: We've heard it on the main site before that couplets and triplets (not longer chippers) should make up the bulk of your training, and it seems to be the case for these programs. It is interesting, however, that the main site averages significantly more movements per metcon that CFNE or Outlaw, neither of whom programmed chippers often. Prior work I've done ("Are Certain Events 'Better' Than Other") indicated that chippers were more predictive of overall fitness in competition, so I suppose the theory in training is that each of the movements gets "watered down" too much in a chipper. I'd be curious to know if there is solid evidence to back up this philosophy, although I tend to agree with it. UPDATE: Actually my previous post indicated that workouts with more movements tended to be more predictive of overall fitness, not necessarily that chippers were better than triplets or couplets. In fact, the "best" event through Open and Regionals was 12.3, a triplet.

Surprisingly Similar Balance Across Programs: I was surprised to see that each program generally put the emphasis on the same types of movements. Sure, the main site was a bit lighter on the Olympic lifting and heavier on the basic gymnastics, but in general, things weren't too different. Also note that none of the programs leaned as heavily on the Olympic lifts and basic gymnastics as the Open. Although...

Outlaw Lifts A Lot: One thing that doesn't show up on the comparison above is the total volume of training; it only deals with how the training time is divided. But it's worth pointing out that Outlaw's training goes through many more movements in a typical day than any of the others, and many of them are Olympic lifts. Below is a chart of the at a pure count of how many times the snatch, clean and jerk appeared, regardless of how much it was emphasized within the workout and allowing for multiple appearances in a day.

Keep in mind that the metcons at Outlaw are generally pretty short and the reps per set are generally low in the strength work, so the overall volume is not quite as intense as it may appear. And again, this is only two weeks worth of data. Also, CFNE's stats are a little inflated because they post a workout 7 days a week, and it's doubtful that many athletes are following the program completely without any rest.

Note that I didn't try to compute the time domains for the training programs. This is primarily because it was just too hard. I haven't completed all these workouts and I don't have readily available data (aside from combing through all the comments on each site) to figure out the time domains if it's not an AMRAP or a strength workout. But I can say that Outlaw is virtually entirely under the 12:00 domain, and the other three seem to be in relatively the same proportion as the Open.

In my opinion, this analysis is really just a starting point for trying to understand training from a statistical angle. The data points aren't nice and clean, and admittedly there are some pretty critical assumptions involved that can have a big impact on the analysis (I've tried my best to note them along the way). This was not simple and it was not easy.

In no way is programming the only factor in an athlete's success. Diet, technique, intensity and desire are all keys. Still, I believe there is value in continuing to evaluate how we're training and thinking critically about why we're training that way.

In my opinion, this analysis is really just a starting point for trying to understand training from a statistical angle. The data points aren't nice and clean, and admittedly there are some pretty critical assumptions involved that can have a big impact on the analysis (I've tried my best to note them along the way). This was not simple and it was not easy.

In no way is programming the only factor in an athlete's success. Diet, technique, intensity and desire are all keys. Still, I believe there is value in continuing to evaluate how we're training and thinking critically about why we're training that way.

Note: I'd be very interested in trying to get some information on the training program for athletes (of all skill levels) who competed in last year's Open and plan to compete this year. We can talk theory all we want and look into some successful programs, but good data would really help to understand what types of training really do bring results. Please email me at anders@alumni.wfu.edu if you have any interest in helping me out. I would not be reporting on any individual's or any gym's training or results in the Open, but simply using information about the training program and improvements from 2012 to 2013. Based on the response, I'll try to gauge whether this is feasible this year.

*Finally, here's a chart showing what movements were included in each subcategory. This is not necessarily an exhaustive list, becaues it only includes movements that appeared in one of the four training programs in my analysis:

*Finally, here's a chart showing what movements were included in each subcategory. This is not necessarily an exhaustive list, becaues it only includes movements that appeared in one of the four training programs in my analysis:

Sunday, November 18, 2012

If We're Going to Stick With Points-per-Place, A Suggestion

After the positive response in the past few days to my post about what to expect from the next Games season, I'd like to continue to write more about training for the upcoming season. I don't purport to be an expert trainer, and I'm certainly not going to be prescribing any workouts, but I hope I can provide a different perspective on the Games and get some discussion started on programming for training vs. competition. But, alas, my schedule this past week just did not give me the time to get into that topic in full detail yet.

Today, I've just got a follow-up on my earlier post regarding the CrossFit Games scoring system ("Opening Pandora's Box: Do We Need a New Scoring System"). In fact, this is actually a follow-up to a comment to that post.

Tony Budding of CrossFit HQ was kind enough to stop by and respond to my article, in particular my suggestion that we move to a standard deviation scoring system. You can read my post and Tony's comment in full to get the details, but the long and short of it is this: HQ is sticking with the points-per-place system for the time being. I'd like to keep the discussion going in the future about possibly moving away from this system, but for now, I accept that the points-per-place is here to stay. Tony made some good points, and I understand the rationale, though I stand by my argument.

Anyway... Tony mentioned that they are still working on ways to refine the system. Certain flaws, like the logjams that occurred at certain scores (like a score of 60 on WOD 12.2) are probably fixable with different programming, and there are some tweaks that could be made to address other concerns (for instance, only allowing scores from athletes who compete in all workouts). But I had another thought that would allow us to stick with the points-per-place system while gaining some of the advantages of a standard deviation system.

At the Games for the past two years, the points-per-place has been modified to award points in descending order based on place, with the high score winning (in contrast to the open and regionals, where the actual ranking is added up and the low score wins). In addition, the Games scoring system has wider gaps between places toward the top of the leaderboard. In my opinion, this is an improvement over the traditional points-per-place system because it gives more weight to the elite performances. However, I think we can do a little better.

First, here is my rationale for why we should have wider gaps between the top places. If you look at how the actual results of most workouts are distributed, you'll see the performance gaps are indeed wider at the top end. The graph below is a histogram of results from Men's Open WOD 12.3 last year:

There are fewer athletes at the top end than there are in the middle, so it makes sense to reward each successive place with a wider point gap. However, the same thing occurs on the low end, with the scores being more and more spread out. But the current Games scoring table does not reflect this - the gaps get smaller and smaller the further down the leaderboard you go (the current Open scoring system obviously has equal gaps throughout the entire leaderboard).

Now, another issue with the current Games scoring table is that it's set up to handle only one size of competition (the maximum it could handle is around 60). So let's try to set up a scoring table that will address my concern about the distribution of scores but can be used for a comeptition of any size (even the Open).

Obviously, the pure points-per-place system used in the Open will work on a competition of any size, but what is essentially does is assume we have a uniform distribution of scores. Basically, the point spread between any two places is the same regardless of where you fall in the spectrum. So what happens is the point difference between 100 burpees and 105 burpees becomes much wider than the gap between 50 and 55 or 140 and 145. So my suggestion is this: let's use a scoring table that ranges from 0-100 but reflects a normal (bell-shaped) distribution rather than a uniform (flat) distribution. The graph below shows that same histogram of WOD 12.3 (green), along with a histogram of my suggested scores (red) and a histogram of the current open points (blue). The scale is different on each histogram, but there are 10 even intervals for each, so you can focus on how the shapes line up.

You can see that the points awarded with the proposed system are much more closely aligned with the actual performances than the current system. And this was done without using the actual performances themselves - I just assumed the distribution of performances was normal and awarded points, based on rank, to fit the assumed distribution.

Now, you may be asking, how well does this distribution fare when we limit the field to only the elite athletes? Well, the shape does not tend to match up as well as we saw in the graph above. Part of this is due to the field simply being smaller, so there is naturally more opportunity for variance from the expected distribution. However, for almost every event in last year's Games, there is no question that the normal distribution is a better fit than the current Games scoring table. The chart below shows a histogram the actual results from the men's Track Triplet along with the distribution of scores using the proposed scoring table and the current scoring table. I have displayed the distribution of scores from the scoring table with lines rather than bars to make the various shapes easier to discern.

As stated above, we do not perfectly match the actual distribution of results. But clearly the actual results are better modeled with the normal distribution than with the current scoring table. As further evidence, the R-squared between the actual results and the proposed scoring table is 96.0%; the R-squared between the actual results and the current scoring table is only 83.9%. If we make this same comparison for each of the first 10 events for men and women (excluding the obstacle course, which was a bracket-style tournament), the R-squared was higher with the proposed scoring table than with the current table, with the exception of the women's Medball-HSPU workout.

I believe this proposed system, while not radically different than our current system, would be an improvement but would not have any of the same issues that concerned HQ about the standard deviation system. While the math used to set up the scoring system may be difficult for many to digest, that's all done behind the scenes and the resulting table is no more difficult to understand than the current Games scoring table, especially if we round all scores to the nearest whole number. If used in the Open, we'd almost certainly have to go out to a couple decimal places, but I think otherwise this system would work fine. And since we are still basing the scores on the placement and not the actual performance, this system also does not allow, as Tony said, "outliers in a single event [to] benefit tremendously." It does, however, reward performances at the top end (and punish performances at the low end) more than the current system.

I appreciate the fact that Tony took the time to review my prior work, and I hope that he and HQ will consider what I've proposed here.

*Below is the actual table (with rounding) that would be used in a field of 45 people (men's Games this year), compared with the current system.

Today, I've just got a follow-up on my earlier post regarding the CrossFit Games scoring system ("Opening Pandora's Box: Do We Need a New Scoring System"). In fact, this is actually a follow-up to a comment to that post.

Tony Budding of CrossFit HQ was kind enough to stop by and respond to my article, in particular my suggestion that we move to a standard deviation scoring system. You can read my post and Tony's comment in full to get the details, but the long and short of it is this: HQ is sticking with the points-per-place system for the time being. I'd like to keep the discussion going in the future about possibly moving away from this system, but for now, I accept that the points-per-place is here to stay. Tony made some good points, and I understand the rationale, though I stand by my argument.

Anyway... Tony mentioned that they are still working on ways to refine the system. Certain flaws, like the logjams that occurred at certain scores (like a score of 60 on WOD 12.2) are probably fixable with different programming, and there are some tweaks that could be made to address other concerns (for instance, only allowing scores from athletes who compete in all workouts). But I had another thought that would allow us to stick with the points-per-place system while gaining some of the advantages of a standard deviation system.

At the Games for the past two years, the points-per-place has been modified to award points in descending order based on place, with the high score winning (in contrast to the open and regionals, where the actual ranking is added up and the low score wins). In addition, the Games scoring system has wider gaps between places toward the top of the leaderboard. In my opinion, this is an improvement over the traditional points-per-place system because it gives more weight to the elite performances. However, I think we can do a little better.

First, here is my rationale for why we should have wider gaps between the top places. If you look at how the actual results of most workouts are distributed, you'll see the performance gaps are indeed wider at the top end. The graph below is a histogram of results from Men's Open WOD 12.3 last year:

There are fewer athletes at the top end than there are in the middle, so it makes sense to reward each successive place with a wider point gap. However, the same thing occurs on the low end, with the scores being more and more spread out. But the current Games scoring table does not reflect this - the gaps get smaller and smaller the further down the leaderboard you go (the current Open scoring system obviously has equal gaps throughout the entire leaderboard).

Now, another issue with the current Games scoring table is that it's set up to handle only one size of competition (the maximum it could handle is around 60). So let's try to set up a scoring table that will address my concern about the distribution of scores but can be used for a comeptition of any size (even the Open).

Obviously, the pure points-per-place system used in the Open will work on a competition of any size, but what is essentially does is assume we have a uniform distribution of scores. Basically, the point spread between any two places is the same regardless of where you fall in the spectrum. So what happens is the point difference between 100 burpees and 105 burpees becomes much wider than the gap between 50 and 55 or 140 and 145. So my suggestion is this: let's use a scoring table that ranges from 0-100 but reflects a normal (bell-shaped) distribution rather than a uniform (flat) distribution. The graph below shows that same histogram of WOD 12.3 (green), along with a histogram of my suggested scores (red) and a histogram of the current open points (blue). The scale is different on each histogram, but there are 10 even intervals for each, so you can focus on how the shapes line up.

You can see that the points awarded with the proposed system are much more closely aligned with the actual performances than the current system. And this was done without using the actual performances themselves - I just assumed the distribution of performances was normal and awarded points, based on rank, to fit the assumed distribution.

Now, you may be asking, how well does this distribution fare when we limit the field to only the elite athletes? Well, the shape does not tend to match up as well as we saw in the graph above. Part of this is due to the field simply being smaller, so there is naturally more opportunity for variance from the expected distribution. However, for almost every event in last year's Games, there is no question that the normal distribution is a better fit than the current Games scoring table. The chart below shows a histogram the actual results from the men's Track Triplet along with the distribution of scores using the proposed scoring table and the current scoring table. I have displayed the distribution of scores from the scoring table with lines rather than bars to make the various shapes easier to discern.

As stated above, we do not perfectly match the actual distribution of results. But clearly the actual results are better modeled with the normal distribution than with the current scoring table. As further evidence, the R-squared between the actual results and the proposed scoring table is 96.0%; the R-squared between the actual results and the current scoring table is only 83.9%. If we make this same comparison for each of the first 10 events for men and women (excluding the obstacle course, which was a bracket-style tournament), the R-squared was higher with the proposed scoring table than with the current table, with the exception of the women's Medball-HSPU workout.

I believe this proposed system, while not radically different than our current system, would be an improvement but would not have any of the same issues that concerned HQ about the standard deviation system. While the math used to set up the scoring system may be difficult for many to digest, that's all done behind the scenes and the resulting table is no more difficult to understand than the current Games scoring table, especially if we round all scores to the nearest whole number. If used in the Open, we'd almost certainly have to go out to a couple decimal places, but I think otherwise this system would work fine. And since we are still basing the scores on the placement and not the actual performance, this system also does not allow, as Tony said, "outliers in a single event [to] benefit tremendously." It does, however, reward performances at the top end (and punish performances at the low end) more than the current system.

I appreciate the fact that Tony took the time to review my prior work, and I hope that he and HQ will consider what I've proposed here.

*Below is the actual table (with rounding) that would be used in a field of 45 people (men's Games this year), compared with the current system.

**MATH NOTE: In case you were wondering, here is the actual formula I used in Excel to generate the table:

POINTS = normsinv(1 - (placement / total athletes) + (0.5 / total athletes)) * (50 / normsinv(1 - (0.5 / total athletes)) + 50

This first part gives us the expected number of standard deviations from the mean, given the athlete's rank. Next we multiply that by 50 and divide by the expected number of standard deviations from the mean for the winner (this will give the winner 50 points and last place -50 points). Then we add 50 to make our scale go from 0-100.

Monday, September 24, 2012

What to Expect From the 2013 Open and Beyond

Assuming we can expect the Open to begin in late February again in 2013, we are now officially closer to next year's Open than we are to last year's. It's time to stop looking back at the 2012 Games season and start looking ahead to next year. I've written extensively about the elite athletes, but most of us who follow the sport closely are competitors ourselves, and this post is designed to understand the qualification process from the standpoint of someone planning to compete this coming season. This isn't about predicting the winners, it's about knowing what to expect and where to place your focus.

Now, seeing as don't have a direct line to Dave Castro and Tony Budding, I don't know what they're thinking for next year. But we do have two years and 6 competitions of data that can help inform us about what they're likely to throw at us in a few months. Let's start by looking at the last two years from the simplest, and possibly the most useful, angle: what movements have we seen the past two years, and how often have we seen them. The following chart shows every movement tested in the past two years along with the weight given to each movement. As I've done before, for each workout, I break it down into the movements involved and give each "station" equal weight. For example, on Open WOD 3 last year, box jumps, toes-to-bar and jerk each received a weight of 0.33. On Open WOD 1, burpees received a weight of 1.00 since it was the only movement.

This chart is a great starting point for understanding what HQ is testing when they're testing for the fittest on Earth.

Now, seeing as don't have a direct line to Dave Castro and Tony Budding, I don't know what they're thinking for next year. But we do have two years and 6 competitions of data that can help inform us about what they're likely to throw at us in a few months. Let's start by looking at the last two years from the simplest, and possibly the most useful, angle: what movements have we seen the past two years, and how often have we seen them. The following chart shows every movement tested in the past two years along with the weight given to each movement. As I've done before, for each workout, I break it down into the movements involved and give each "station" equal weight. For example, on Open WOD 3 last year, box jumps, toes-to-bar and jerk each received a weight of 0.33. On Open WOD 1, burpees received a weight of 1.00 since it was the only movement.

This chart is a great starting point for understanding what HQ is testing when they're testing for the fittest on Earth.

In case you were not aware, you better get your Olympic lifting in order if you want to be competitive in CrossFit. Including the jerk, the Olympic lifts were worth about 20% of all events in the past two years. That's not likely to change. We've seen snatch tested in each the Open, Regionals and Games both of the last two years.

What's also clear is that the pull-up is still important, as are an array of other bodyweight movements, including muscle-ups, burpees and toes-to-bar. Throw in running and double-unders, and we're up over 50% of the total weight (after counting the Olympic lifts). You've got to be good at everything, but those are the basics.

However, these include all competitions. Because of logistic restrictions and the relatively lower skill levels, the Open includes a much narrower list of movements. Here's what we have seen from the Open the past two years.

There may a couple of other movements thrown in this year, but not many. I highly doubt we'll see running or swimming, and some other staple movements like rowing, handstand push-ups and rope climbs are not likely for one reason or another (I'm still holding out hope for HSPU's, but I think the odds are slim). Even the swing hasn't shown up in the Open so far.

So the main takeaway here is that for the Open, you basically need to be able to Olympic lift and handle some basic bodyweight movements. You need to be able to do those things very well, but if your handstand walk isn't on point yet, you'll probably be OK.

But we can look deeper. This only tells us what movements we're likely to see. For the lifting movements, there is another aspect we need to consider: the loading.

To understand how "heavy" certain workouts are compared to others, we can't simply look at the loading in a vacuum. The same weight might make for a very heavy thruster but a very easy deadlift. To solve this problem, I started asking around my gym for max lifts on a variety of common lifts. I used the maxes of those at my gym, along with a bit of research into some of the elite athletes and my own personal experience, to develop relativities between the lifts. I'd love to get a bigger sample in the future and refine these numbers, but for now, we'll work with what we have.

Once I got these relativities, I was able to set a "base" weight for each lift. With these base weights, I could then compare the loads we saw in the Open (and the Regionals and Games) and get a feel for how heavy they really are. Along those same lines, we can see what types of weights we could expect, on average, this year. Based on the past two years*, here are the "expected" weights this year.

Keep in mind, those are just the averages. We've seen relatively heavier and lighter loads than those in the past. Based on the heaviest workout we've seen (the squat clean and jerk from 2011) to date, we can make an educated guess about the heaviest weights we might see this year. Adding on a 5% margin in case Castro gets crazy, here are the heaviest weights you can reasonably expect to see required in a workout (rounded to nearest 5).

Clean: 180 (men), 120 (women)

Jerk: 175, 115

Snatch: 135, 90

Deadlift: 320, 215

Thruster: 145, 95

Overhead squat: 155, 100

Back squat: 255, 170

Front squat: 215, 140

Now, I know we're mainly focused on the Open, but let's give these numbers a little perspective by looking at the Regionals and the Games as well. I've calculated the average relative weight seen at each competition for the past two years. Things got a bit tricky at the Games with movements like the sled push, so there were some judgement calls**. Nonetheless, this gives us an idea of the relationship between the various levels of competition.

A 1.0 is equal to the "base" weights in the charts above (135-lb. clean, 100-lb. snatch, etc.). These charts include metcons only (I'll discuss the max effort lifts in a bit, but of course there have not been any in the Open).

UPDATE 12/10/12 - This graph originally had incorrect values for the Open (they were too low). The error was only in this graph, not in the underlying numbers mentioned elsewhere.

As you can see, the loading gets substantially heavier once you get beyond the regionals. This makes sense intuitively to anyone who's followed the Games season the past two years. The average weights you could expect to see in a men's metcon at the regionals include a 155-lb. clean, a 275-lb. deadlift and a 185-lb. front squat. Those are just the averages - we've seen much heavier.

Finally, let's combine the two concepts of loading and movements. What I was curious about understanding was just how much emphasis was placed on lifting, and lifting heavy, in each competition for the past two years. Consider the 2011 and 2012 regionals: based on the average weight load in metcons, the competitions were roughly equal in terms of load. However, as I thought about it, it seemed intuitive that the 2012 regional was much "heavier." After all, we saw 225-lb. cleans, 345-lb. deadlifts and 100-lb. DB snatches. Additionally, we had a max-effort snatch. The 2011 regional was heavy (315-lb. deadlifts, 135-lb. snatches, max thruster), but it didn't seem as heavy.

The reason? The 2012 regional had more lifting, although not necessarily heavier lifting. And that's what really matters if we're trying to judge these things. When Chris Spealler, a little guy, says the regional programming was really tough for him this year, what he means is that there were a lot of lifts and they were awfully heavy.

The following chart shows the ratio of bodyweight movements to lifts in each of the last six competitions.

We can see that the 2012 Regional has had the biggest lifting bias, by a decent margin, of any competition in the past two years. Using this information and the average loading we developed earlier, we can get a total picture of how much heavy lifting was emphasized at each competition. The following metric, which I've called Load-Based Emphasis on Lifting (LBEL), is calculated by taking the average weight load (including max effort lifts***) and multiplying that by the percent of the movements that are lifts. The numbers here are harder to interpret, but this may help: "Fran" for men is about 0.45, "Grace" is 1.0 and "Cindy" is 0.0. Do all three of those for a competition, and you'd get about 0.5 for the competition as a whole.

Here are the LBEL scores for the past two years.

You can see that the 2012 Regionals was by far the top score. You may also notice that the Games are often equal to or lower than the Open. This is because the Games often focuses heavily on bodyweight movements not seen at earlier levels (long runs, obstacle course, deficit HSPU, handstand walks, etc.). The Games is not "easier" than the Open by any stretch. The loads you do see at the Games would be too much for 95% of the athletes who compete in the Open, and the strength demands of the bodyweight movements are extreme. But if you want to know which programming more favors a bigger, stronger athlete over a smaller, better conditioned athlete, I think they are actually pretty similar.

The main takeaways here are these: 1) For the Open, the emphasis is on Olympic lifting and some basic bodyweight movements; 2) The loadings at the Open are moderate, but lifting is emphasized quite a bit; 3) Things are likely to get heavy at the regionals; 4) The Games has more emphasis on bodyweight movements, but be prepared to lift heavy when you do lift; 5) It's time to get back to training - only 5 months left until the 2013 season begins!

Math notes:

*For the snatch workout this year, the weights varied based on how far you got in the workout. I looked at the top 1,500 overall finishers (roughly the regional qualifiers), and calculated an "average" load throughout the workout. The reason for using the top 1,500 is that I wanted this post to be from the perspective of someone attempting to qualify this year. The average weight came out to be 128 lbs. for men and 76 lbs. for women. In calculating the average, I looked at the total amount of weight lifted, then looked at how much of that weight was lifted at each level. For instance, if you got a score of 60, that's 30x75 = 2,250 lbs. lifted at 75 lbs. and 30x135 = 4,050 lbs. lifted at 135 lbs. Therefore, 64% was lifted at 135 and 36% was lifted at 75. The average would be .64x135 + .36x75 = 113.6 lbs.

**Here are the relative weights I assigned to the lifts not listed on the original "base" weight chart (these are the men's weights, women's were generally reduced to about 2/3 of these):

Swings (53 lbs) .75, DB ground-to-overhead (45 lb DBs) 1.00, weighted lunge (45 lbs) 1.00, DB snatch (100 lbs) 1.50, farmer's walk (100 lb. DBs) 1.50, weighted pull-up 1.08, water jug carry 1.50, dog sled 2.00, sumo deadlift high pull (108 lbs) 1.14, sled pull with rope 2.00, ball toss (4 lbs) 0.50, medicine ball clean (150 lbs) 1.5, blocking sled push 1.50, sledgehammer 0.75.

If you'd like more info on how I arrived at these, let me know and I'll expand on my thought process.

**For the max effort lifts, I took the average result for each competitor. Max effort lifts are tricky because they are dependent on who is doing the workout (similar to the Open snatch WOD). In general, I'd expect most max effort lifts to be about twice the average weight load seen at the competition. That would mean the metcons are generally done at about 50% of each person's max, which is pretty typical if loads are scaled properly.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

Quick Hits: What Can We Learn from the Standard Deviation System?

After posting a lengthy essay on the benefits of switching to the Standard Deviation scoring system, I felt like I had to apply the scoring system to this year's Games and see what I could learn. Obviously it would be interesting to re-calculate the final standings with the new system, but I think there are a few other things that we can do with this new system. Because we are now scoring based on performance rather than simply rank, this new system allows us to compare events and individual performances across separate events. I'll try to keep this one relatively short, just hitting on the highlights of what I found.

Remember all events are converted to a power output (think reps or stations per minute, instead of time to completion). This was a painful process b/c of the way HQ scored athletes who did not finish a workout in the allotted time. I also generally assumed every "station" was worth equal weight (so on the Medball HSPU, the 8 medball cleans were equal to the 7 HSPU). This was the simplest solution. On the obstacle course, because I was basically forced into using the rankings and not the actual performances, I assumed a normal distribution and converted the ranks to an equivalent number of standard deviations from average. If HQ were to adopt this scoring system, they'd have to make the decision on how to weight the stations.

Anyway, enough with the math and onto the results:

Which event had the widest spread?

We can judge this based on the coefficient of variation for each event, which is the standard deviation divided by the average.

For the men, the widest spread came in the Medball-HSPU workout. The average score was 0.60 stations/minute (9:56) and the standard deviation was 0.18 stations per minute, giving us a coefficient of variation of 29%.

For the women, the widest spread also came in the Medball-HSPU workout. The average score was 0.56 stations/minute (which translates to finishing in 10:48, which is over the cap) and the standard deviation was 0.32 stations/minute, giving us a coefficient of variation of 58%. This shouldn't be surprising, considering the winning time was just over 5 minutes, but more than half the field didn't even finish.

Which event had the tightest spread?

For the men, the tightest spread came in the sprint. The average score was 6.60 meters/second (45.48 seconds) and the standard deviation was just 0.32 meters/second. The coefficient of variation was 5%. The second-tightest was Pendleton 2 at 8%.

For the women, the tightest spread also came in the sprint. The average score was 5.83 meters/second (51.49 seconds) and the standard deviation was just 0.31 meters/second. The coefficient of variation was 5%. The second-tightest was the clean ladder at 8%.

What was the most dominating individual performance over the field?

We'll measure this based on the number of standard deviations from the mean by the winner.

For the men, this came in the Rope-Sled event, where Matt Chan had a result of 1.32 stations/minute (7:33.6), which was 2.80 standard deviations above the average score of 0.87 stations/minute (11:48).

For the women, the most dominating performance came in the clean ladder, where Elisabeth Akinwale had a score of 235.6, which was 2.42 standard deviations above the average of 195.76.

What were the widest and tightest margins between first and second in an event?

Similarly, we're looking for the standard deviations between the first and second place finish.

For the men, the widest gap came in the Rope-Sled event. Chan was 0.89 standard deviations ahead of second-place Jason Khalipa, who had 1.18 stations/minute (8:27.0). The closest event came in the sprint, where Nate Schrader finished in 7.14 meters/second (42.0 seconds), just 0.11 standard deviations ahead of second-place David Levey at 7.11 meters/second (42.2 seconds).

For the women, the widest gap came in Elizabeth. Deborah Cordner Carson had a score of 25.09 reps/minute (3:35.2), which was 1.04 standard deviations ahead of second-place finisher was Kristan Clever at 21.79 reps/minute (4:07.8). The tightest race came in the clean ladder, where Lindsay Valenzuela basically tied Akinwale (she had the same lift but completed one fewer deadlift).

*In the events before any cuts, the biggest gap on the women's side came in the ball toss, where Cheryl Brost's score of 61 points was 0.53 standard deviations ahead of second-place Elizabeth Akinwale (57 points).

Seriously, what do the revised standings look like?

OK, I'm going to caveat this by saying that it's not totally fair to say the standings would have looked like this if we had scored the event differently. Obviously the athletes may have approached workouts differently had they been higher or lower in the standings, and they may have pushed harder for those extra few points in each event when more than just a simple ranking was involved. I think this is probably the least important thing we can learn from the new scoring system, since the event is done and there's nothing we can do to change it.

But that being said, for amusement purposes only, here is your revised top 12 for men and women (no one from outside the top 12 could move into the top 12 because of the cuts):

*UPDATED 1/19/2013 - An error in the Obstacle Course scoring has been fixed and these have been revised. Only major shift was Foucher going from 4th to 2nd on the women's side. Otherwise pretty similar to prior results.

Men

1. Rich Froning (15.49)

2. Matt Chan (11.97)

3. Scott Panchik (8.75)

4. Jason Khalipa (7.99)

5. Kyle Kasperbauer (6.96)

6. Dan Bailey (6.57)

7. Austin Malleolo (5.27)

8. Marcus Hendren (4.82)

9. Nate Schrader (4.23)

10. Graham Holmberg (4.07)

11. Ben Smith (2.77)

12. Chad Mackay (1.78)

Women

1. Annie Thorisdottir (13.70)

2. Julie Foucher (9.19)

3. Talayna Fortunato (8.77)

4. Kristan Clever (8.55)

5. Camille Leblanc-Bazinet (6.14)

5. Lindsey Valenzuela (5.65)

6. Elisabeth Akinwale (5.60)

8. Valerie Voboril (5.28)

9. Jenny Davis (4.74)

10. Rebecca Voigt (2.84)

11. Stacie Tovar (1.43)

12. Christy Phillips (0.75)

*These scores assume that the ball toss, broad jump and sprint were given half the value of the other events.

Remember all events are converted to a power output (think reps or stations per minute, instead of time to completion). This was a painful process b/c of the way HQ scored athletes who did not finish a workout in the allotted time. I also generally assumed every "station" was worth equal weight (so on the Medball HSPU, the 8 medball cleans were equal to the 7 HSPU). This was the simplest solution. On the obstacle course, because I was basically forced into using the rankings and not the actual performances, I assumed a normal distribution and converted the ranks to an equivalent number of standard deviations from average. If HQ were to adopt this scoring system, they'd have to make the decision on how to weight the stations.

Anyway, enough with the math and onto the results:

Which event had the widest spread?

We can judge this based on the coefficient of variation for each event, which is the standard deviation divided by the average.

For the men, the widest spread came in the Medball-HSPU workout. The average score was 0.60 stations/minute (9:56) and the standard deviation was 0.18 stations per minute, giving us a coefficient of variation of 29%.

For the women, the widest spread also came in the Medball-HSPU workout. The average score was 0.56 stations/minute (which translates to finishing in 10:48, which is over the cap) and the standard deviation was 0.32 stations/minute, giving us a coefficient of variation of 58%. This shouldn't be surprising, considering the winning time was just over 5 minutes, but more than half the field didn't even finish.

Which event had the tightest spread?

For the men, the tightest spread came in the sprint. The average score was 6.60 meters/second (45.48 seconds) and the standard deviation was just 0.32 meters/second. The coefficient of variation was 5%. The second-tightest was Pendleton 2 at 8%.

For the women, the tightest spread also came in the sprint. The average score was 5.83 meters/second (51.49 seconds) and the standard deviation was just 0.31 meters/second. The coefficient of variation was 5%. The second-tightest was the clean ladder at 8%.

What was the most dominating individual performance over the field?

We'll measure this based on the number of standard deviations from the mean by the winner.

For the men, this came in the Rope-Sled event, where Matt Chan had a result of 1.32 stations/minute (7:33.6), which was 2.80 standard deviations above the average score of 0.87 stations/minute (11:48).

For the women, the most dominating performance came in the clean ladder, where Elisabeth Akinwale had a score of 235.6, which was 2.42 standard deviations above the average of 195.76.

What were the widest and tightest margins between first and second in an event?

Similarly, we're looking for the standard deviations between the first and second place finish.

For the men, the widest gap came in the Rope-Sled event. Chan was 0.89 standard deviations ahead of second-place Jason Khalipa, who had 1.18 stations/minute (8:27.0). The closest event came in the sprint, where Nate Schrader finished in 7.14 meters/second (42.0 seconds), just 0.11 standard deviations ahead of second-place David Levey at 7.11 meters/second (42.2 seconds).

For the women, the widest gap came in Elizabeth. Deborah Cordner Carson had a score of 25.09 reps/minute (3:35.2), which was 1.04 standard deviations ahead of second-place finisher was Kristan Clever at 21.79 reps/minute (4:07.8). The tightest race came in the clean ladder, where Lindsay Valenzuela basically tied Akinwale (she had the same lift but completed one fewer deadlift).

*In the events before any cuts, the biggest gap on the women's side came in the ball toss, where Cheryl Brost's score of 61 points was 0.53 standard deviations ahead of second-place Elizabeth Akinwale (57 points).

Seriously, what do the revised standings look like?

OK, I'm going to caveat this by saying that it's not totally fair to say the standings would have looked like this if we had scored the event differently. Obviously the athletes may have approached workouts differently had they been higher or lower in the standings, and they may have pushed harder for those extra few points in each event when more than just a simple ranking was involved. I think this is probably the least important thing we can learn from the new scoring system, since the event is done and there's nothing we can do to change it.

But that being said, for amusement purposes only, here is your revised top 12 for men and women (no one from outside the top 12 could move into the top 12 because of the cuts):

*UPDATED 1/19/2013 - An error in the Obstacle Course scoring has been fixed and these have been revised. Only major shift was Foucher going from 4th to 2nd on the women's side. Otherwise pretty similar to prior results.

Men

1. Rich Froning (15.49)

2. Matt Chan (11.97)

3. Scott Panchik (8.75)

4. Jason Khalipa (7.99)

5. Kyle Kasperbauer (6.96)

6. Dan Bailey (6.57)

7. Austin Malleolo (5.27)

8. Marcus Hendren (4.82)

9. Nate Schrader (4.23)

10. Graham Holmberg (4.07)

11. Ben Smith (2.77)

12. Chad Mackay (1.78)

Women

1. Annie Thorisdottir (13.70)

2. Julie Foucher (9.19)

3. Talayna Fortunato (8.77)

4. Kristan Clever (8.55)

5. Camille Leblanc-Bazinet (6.14)

5. Lindsey Valenzuela (5.65)

6. Elisabeth Akinwale (5.60)

8. Valerie Voboril (5.28)

9. Jenny Davis (4.74)

10. Rebecca Voigt (2.84)

11. Stacie Tovar (1.43)

12. Christy Phillips (0.75)

*These scores assume that the ball toss, broad jump and sprint were given half the value of the other events.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Opening Pandora's Box: Do we need a new scoring system?

Until now, I haven't touched on what seems to be the most controversial topic when the Games roll around each year: the scoring system. I have been mainly focused on evaluating what happened this year and predicting results based on the system we have. But there is no doubt that the scoring system in place, which is based entirely on rank, has its flaws. The question is this: can we devise a system that is truly better?

Update: Before I get any further, I'd like to mention that the 2012 Open data I am using is from Jeff King, downloaded from http://media.jsza.com/CFOpen2012-wk5.zip. Thanks a ton to Jeff for gathering all the data. Much of this analysis would not be possible without it.

First, let me lay out four key flaws I see in the points-per-place system:

1) The results are heavily dependent on who you include in the field. Take the Games competitors, for example, and rank them based on their Open performance. You get very different results if you score each event based on the athletes' rank among the entire Open field than if you score each event based on the athletes' rank among only the Games competitors. Neal Maddox would move from 5th using the entire field to 2nd using only Games competitors, Rob Forte would move from 15th to 25th and Marcus Hendren would move from 34th to 16th. This is a problem.

2) There is no reward for truly outstanding performances. In the Open, Scott Panchik did 161 burpees in 7 minutes. The next closest mens Games competitor was Rich Froning at 141. In a field with only Games competitors, Panchik would only gain ONE point on Rich. He was not rewarded at all for any burpees beyond 142 (even with all Games competitors included, he only beat Froning by 33 spots, a relatively slim margin among 30,000+ competitors).

3) Along the same lines, tiny increments can be worth massive points if the field is bunched in one spot or another. If I had performed one more burpee (I did 104), for instance, I would have gained 857 spots worldwide. The difference between 70 and 71 burpees (a larger proportional increase in work output) was worth only 327 spots. And the gap between 141 and 161 was only 33 spots.

4) Other athletes can have a huge impact on the outcome between two competitors. Why should the differential between Rich Froning and Graham Holmberg come down to how many other competitors finished between their scores on a certain event? If those other competitors hadn't even been competing, it wouldn't change how Rich and Graham compared to each other.

Now, while I don't agree with everything Tony Budding says, I think he brought up a good point when he defended the scoring system on the CrossFit Games Update show earlier this year. Regardless of whether it has some mathematical imperfections, the fact of the matter is the points-per-rank scoring system is very easy to understand and very easy to implement. Watching the Olympic Decathlon, which has been refining its scoring system for years, reminded me why the points-per-place system isn't so bad. Unless you have a scoring table and a calculator handy, the Decathlon scores seem awfully mysterious. So if we're going to come up with a scoring system to replace the points-per-place system, I believe it has to be easy for viewers and athletes to understand.

That being said, we can learn from what the Decathlon has done. The idea behind the Decathlon scoring system is to attempt to weight each of the events equally, so that performances of equal skill level in each event yield similar point totals. Beyond that, the same scoring system should be applicable to athletes ranging from beginners to elite athlete. Additionally, the scoring system for all events is at least slightly "progressive" - this means that as performances get closer and closer to world record levels, each increment of performance more and more valuable. For instance, the difference in score between a 11-second to a 12-second 100 meters is wider than the difference between a 12-second and a 13-second 100 meters.

Each event is scored based on a formula, taking one of two forms

Points for running events = a * (b - Time)^c

Points for throws/jumps = a * (Distance - b)^c

For each, the value of b represents a beginner level result (for instance, 18.00 seconds in the men's 100 meters), and c is greater than 1, which is the reason the scores are progressive. Certain events are more progressive than others; generally, the running events are more progressive than the throws. Here is a chart showing the point value of times in the 100 meters.