What you need to know from this post:

- On average, athletes that compete in the Open in multiple years improve their rank percentile in the second year, but their absolute ranking declines.

- The more years an athlete competes in the Open, the less they improve their percentile ranking in subsequent years, although the average improvement is still positive.

- There is pretty strong evidence that if the Open has a higher load-based emphasis on lifting (LBEL), this will favor taller and heavier athletes. If the Open has a lower LBEL, this will favor smaller and lighter athletes.

- It is unclear how age is related to an athlete's percentile ranking improvement from year-to-year.

Today I want to get into a topic that has interested me for some time. Many readers of this site have been competing in the Open for several years and likely have used their performance each year to judge how much their fitness has improved from the past year. There are two underlying assumptions that we use here:

- The Open is a pretty good test of overall fitness;

- Each year of the Open is a relatively similar test of fitness, compared to other years.

I'm going to leave the first assumption unchallenged today, although there could certainly be debate about that. But let's assume that the Open is indeed a good test of fitness. What I will try to do today, using data from 2011-2014, is try to test the second assumption and get a feel for how much impact, if any, variations in the programming might have from year-to-year. Along the way, I'll also look for other interesting observations about how athletes are improving across multiple years in the Open.

Before we get into the results, here's a quick background on the data I'm using and my basic methodology:

- For both men and women, I started with the Open results for athletes under the age of 55 (meaning no scaling in the Open).

- I removed any athletes whose first/last name combination was not unique. This is due to the fact that my data does not have any other identifiers for each athlete. Since there are something like 9 or 10 Ben Smith's, I just threw them all out.

- I removed all athletes that did not complete all five events.

Next, I split up the analysis into six cohorts: 2013-to-2014 male, 2013-to-2014 female, 2012-to-2013 male, 2012-to-2013 female, 2011-to-2012 male and 2011-2012 female (an athlete could be multiple cohorts). For each section, I identified athletes that competed in both years. For all athletes that submitted it, I also mapped on age, height and weight information from 2013 (except for the 2011-2012 cohorts, in which case I used the 2012 information). I had to make the simplifying assumption that an athlete's weight did not change from year-to-year, which is probably not true for some athletes.

OK, with the background out of the way, let's move onto the findings. The first thing I wanted to know was just how much improvement athletes were making from year-to-year. The initial results might surprise you:

On average, athletes who continued from one year to the next actually finished lower in the second year than in the first. In fact, between 60-80% of athletes had a lower rank in the subsequent year across all six cohorts.

So what gives? Well, the key here is that the field has been expanding, nearly doubling in size each year. The easy way to account for that is to look at the change in an athlete's percentile rank from year-to-year. If an athlete is 5,000th out of 50,000 in 2013 and 8,000th out of 100,000 in 2014, then the percentile rank actually shows an increase of 1% (5% to 4%), despite the 3,000-spot drop in absolute rank.

Now we see that in general, athletes are improving year-to-year, although it became a bit more difficult each year. Approximately 89% of athletes improved their percentile rank from 2011-2012, compared to 80% from 2012-to-2013 and 71% from 2013-to-2014.

Each year, we have more and more athletes who have been competing for several years. Most of us who have been CrossFitting for a long time know that making incremental improvements becomes harder and harder (thought not impossible) as the years go on. For evidence of this, I looked at the average percentile improvement from 2013-to-2014 of athletes who also competed in 2012 vs. those who did not.*

These numbers make it fairly clear that the amount of past Open experience is a factor in how much improvement athletes make from year-to-year in the Open. But how about other variables, such as height, weight or age? This is where things get a little tricky.

First, let's look at age. The three charts below show the average improvement by age for males (orange) and females (blue) in each time period.

From these charts, we see that there is not a simple answer here. In two cases (male 2012-2013 and female 2013-2014), improvements were generally higher at older ages, but in the other four cases, the reverse was true. Across the four cohorts, the correlation between age and percentile rank improvement ranged from -12% to +14%. Unfortunately, the results are not consistent by gender or by year, in which case we might be able to make some sort of generalization about what these results mean. For now, I will simply conclude that there is no clear relationship between age and year-to-year improvement in the Open.

How about height and weight**? Well, again, the results were mixed, but in this case, the mix of results might actually be able to provide some insight. Let's focus on weight for now. Four of the six cohorts did show a clear linear relationship between weight and percentile rank improvement, but the other two did not. Here are charts showing the relationships for those cohorts.

From 2012-to-2013 for females (third chart), it appears that heavier athletes tended to show more improvement than lighter female athletes. In the other three cohorts shown, heavier athletes tended to show less improvement than lighter athletes.

Another way to look at this is by examining the correlation between and percentile rank improvement in each cohort. A positive correlation means that higher weights tend to have higher percentile rank improvements; a negative correlation means that higher weights tend to have lower percentile rank improvements. The correlations for the four cohorts shown above tell the same story: -11% correlation for 2011-2012 males, -15% correlation for 2011-2012 females, +8% correlation for 2012-2013 females and -6% correlation for 2013-2014 males.

What could be the reason for these results?

For each of the Opens, I've evaluated the programming using a few metrics. One that I reference quite frequently is the load-based emphasis on lifting (LBEL). This metric attempts to quantify how "heavy" a CrossFit competition is based on the portion of the competition that was made up of lifts (as opposed to bodyweight movements), as well as how "heavy" those movements were. After seeing the charts above, I went back and looked at the LBEL in each of the years for both males and females. What I found was that in situations where there was a strong negative correlation between weight and improvement, the LBEL decreased significantly, and in situations where there was a strong positive correlation between weight and improvement, the LBEL increased significantly.

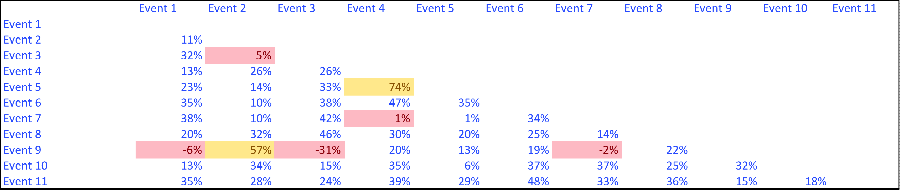

The chart below shows the following for each cohort:

- Percentage change in LBEL;

- Correlation between weight and improvement in percentile rank;

- Correlation between height and improvement in percentile rank; and

- Correlation between age and improvement in percentile rank.

While we still can't seem to tell much about the relationship between age and improvement, this chart above does seem to clearly indicate that a higher LBEL benefits larger athletes and a lower LBEL benefits smaller athletes. Note that the color scales for the percent change in LBEL mirror the weight correlation almost exactly.

While this my seem intuitive, I think it is a very important result to lend credibility to the LBEL metric. It is still my belief that LBEL is not a particularly useful metric when looking at individual events, but when used to evaluate a multi-event competition such as the Open or Regionals, I think it is very useful to help us understand the type of athletes that might benefit from the programming. Keep in mind, of course, that these correlations are relatively small, so there are plenty of other factors that determine how much an athlete will improve from year-to-year.

Obviously, none of this is meant to de-emphasize the importance of training in determining how much an athlete will improve from year-to-year. Rather, this can help us understand all the factors that might be impacting an athlete's improvement, which can in turn help evaluate how successful all that training really was.

[Thanks a lot to Andrew Havko, Michael Girdley and Jeff King for pulling this data for me and/or making it publicly available]

[Thanks a lot to Andrew Havko, Michael Girdley and Jeff King for pulling this data for me and/or making it publicly available]

*I did also take a look briefly at the 2013-2014 improvement for athletes who competed back in 2011. As expected, they were slightly lower than those who just competed in 2012. However, they did still show a positive improvement in their percentile rank, on average.

**Many athletes did not submit their height or weight (or typed in something ridiculous, like 1,000 pounds). Any time I looked at correlations between weight/height and percentile rank improvement, these are based only on the subset of athletes that reported a reasonable height and weight. This ranged from about 50%-80% of the field (women generally reported less often).